¿Hablas español? Una traducción de esta publicación se puede encontrar aquí

Every year more than a million people flock to Washington, DC to see the cherry blossom trees in full bloom around the Tidal Basin. The cherry trees, which were a gift from the Japanese government in 1912, have long been a draw for tourists and locals. Today there are 11 types of non-native flowering cherry trees on the National Mall.

Figure 1. Cherry trees in bloom around the Tidal Basin in Washington, DC. The National Cherry Blossom Festival attracts an estimated 1.5 million visitors a year! Photo: Matthew G. Bisanz, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

While the famous cherry trees were planted in 1912, they weren’t the first cherry trees that arrived from Japan. The first shipment arrived in 1909, but was burned on the grounds of the Washington Monument after the trees were found to be infested with many kinds of non-native pests including scale, thrips, and moths. (Though, a few trees from the 1909 shipment may have been saved for study by entomologists!) The inspection and subsequent destruction of the trees was controversial not only for its dramatic outcome, but because at the time the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) was not authorized to inspect private introductions of plants into the country. These circumstances led Congress to pass the Plant Quarantine Act of 1912, the precursor to today’s Animal Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS). The goal was to prevent harmful organisms from being accidentally introduced into the United States via inspections, quarantines, and continued monitoring. Those same practices are also our best defense against pests on a more local level.

Keeping the cherry trees healthy

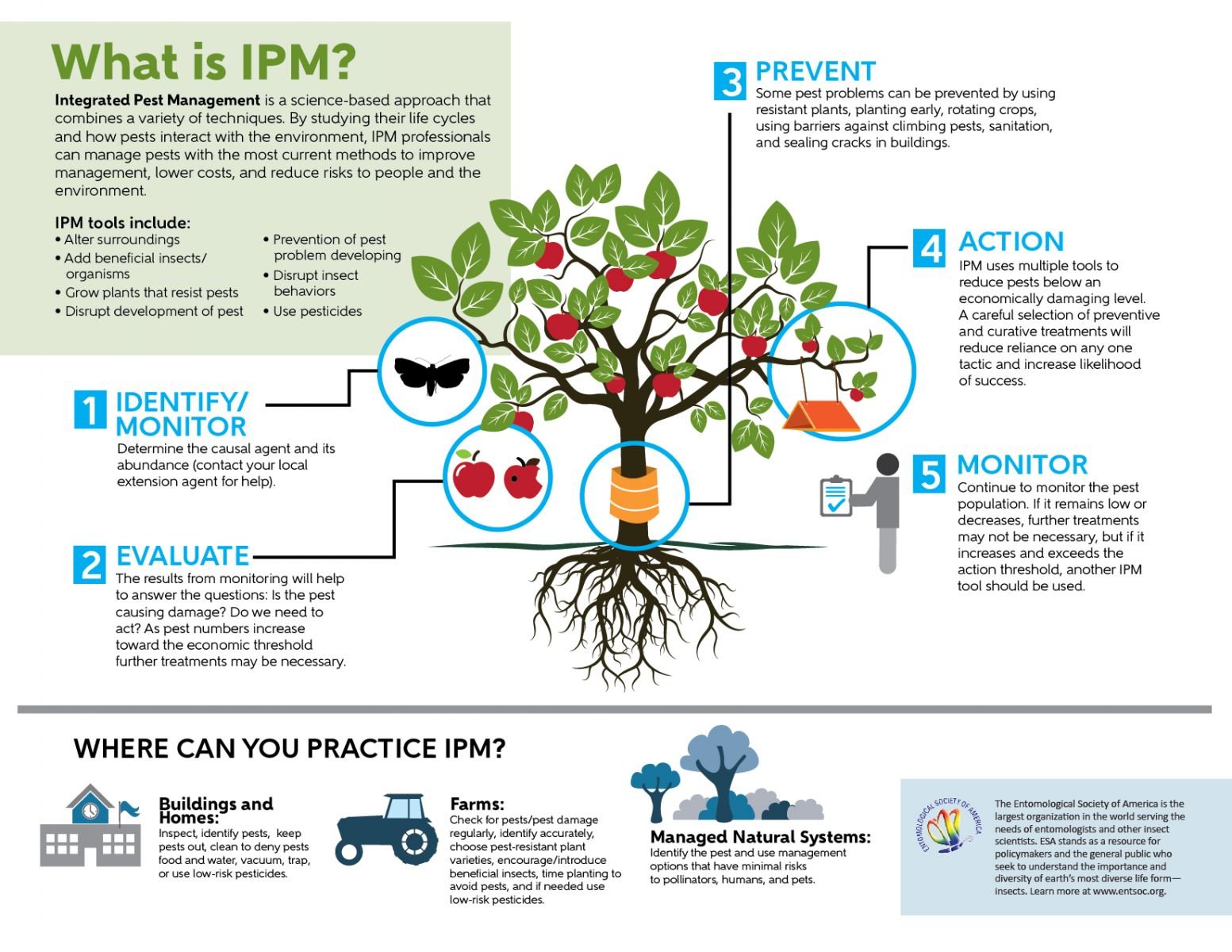

Today the health of the Tidal Basin cherry trees is still closely monitored by National Park Service officials. The foundation of their approach is integrated pest management (IPM). IPM is a sustainable strategy for managing insects based on monitoring trees during the times of year that potential pests are most likely to be a problem. If a pest outbreak that could harm the tree is detected, then multiple complementary tactics are used to keep pests numbers below thresholds that cause substantial harm. If you visited the cherry trees, you could likely find many insects and fungi, but few will be in numbers that would kill a tree – which is the ideal outcome of IPM!

Figure 2. Integrated pest management combines continued monitoring, evaluation, prevention and action to manage insect populations with lower costs and minimal impact on people and the environment. Image: Entomological Society of America

Local populations in a global world

The official shipments of cherry trees from Japan to Washington DC are only a tiny, miniscule fraction of the movement of plants and animals around the globe. While some introductions are accidental, many organisms are moved purposefully, for agriculture or landscaping purposes. Up to 50-70% of non-native species arrived in their new regions with the horticultural trade!

The prevalence of non-native plants is important because native insects might not be able to use the non-native plant species in the same ways, but also because non-native insects can move with the non-native plants, as seen in the doomed 1909 shipment of cherry trees. Monitoring and preventing new pests from establishing on trees native to the eastern US is the most powerful IPM strategy. Once a non-native insect establishes in a new area, it becomes harder to control their populations with IPM, meaning outbreaks can be more likely. The cherry trees are a beautiful and beloved addition to the Washington DC landscape, but they are also a cautionary tale of the effort required to safely add and maintain a plant species in a new environment.

Tracking the blooms this spring

If you want to keep track of the predicted peak bloom time this year check for the National Park Service peak bloom forecast anytime after March 1st and for up-to-date live views check out the #Bloomcam of the tidal basin. If you would prefer a less crowded place to see cherry trees in bloom, the National Arboretum also has a collection of over 70 varieties of cherry trees that bloom all spring long. Keep your eye out for interesting native insects that eat the leaves or pollinate these trees!

Figure 3. Cherry blossoms in full bloom. There are 11 types of cherry trees on the Washington DC National Mall, ranging in color from white to deep pink. Photo: NPSPhoto

Further reading

Cherry Blossoms, Insects, and Inspections, by Kelly Buchanan, Library of Congress

Celebrating 100 Years of Washington, DC’s Cherry Blossoms, by Alyn Keil, USDA

National Park Service

Part 2 of this story is out now! Read it here.